European Investment Bank – the EU’s Northern Rock

Published by Gbaf News

Posted on July 31, 2012

6 min readLast updated: January 22, 2026

Published by Gbaf News

Posted on July 31, 2012

6 min readLast updated: January 22, 2026

At the Brussels EU summit at the end of June David Cameron agreed to President Hollande’s €130bn “growth” plan for the EU (this, in reality, is a “spending” plan). The major part of that “growth” would emerge via increased lending from the European Investment Bank (EIB) to public-sector projects. Possibly as much as an extra €100bn of lending is planned, mostly funded through new bonds issued by the EIB, but with the balance – €10bn – coming in the form of a call on the subscribed capital.

All European Union member states are shareholders in EIB, and they have subscribed to a total of €232bn in capital, of which only €11.6bn had been called prior to this exercise. Since the United Kingdom is a 16% shareholder in EIB, it’s 16% share of a €10bn capital call is EUR1.6bn. In turn, that €1.6bn is part of the UK’s existing uncalled commitment of €35.7bn.

David Cameron has hailed the expansion of EIB’s loan book as good for growth at a time when commercial banks are not lending, and particularly into the private sector.

This is an odd comment since most of EIB lending is to the public sector, and the remainder is guaranteed by banks: EIB does not engage directly with the private sector. However by inserting itself as an intermediary between capital-holders and borrowers it has impinged on the domain of commercial banking, whose role should be assessing credit risk, applying funds to projects that deliver a pay-back and pricing risk accordingly.

EIB, on the other hand, because it directs most of its lending to public-sector projects, plays a major role in expanding the public sector, misdirecting economic resources towards projects that produce little in the way of financial returns, and usurping the role of commercial banks. It does this by:

EIB is the embodiment of the difference between a free market economy and a social market economy, in which the government and not the marketplace makes major decisions about allocation of resources. EIB embodies everything the EU claims not to be: a centralised monolith bearing significant resemblance to the Soviet Union.

Soviet projects, like the White Sea canal, drew their subsidy – the difference between costs and returns – from Gulag slave labour. The EIB draws its subsidy from recourse to the taxpayer:

There is thus no moral hazard in either the EIB’s borrowing or its lending. On both sides it abuses the credit capacity of the ultimate private sector – the taxpayer – to transfer resources to the public sector.

The EIB has been in operation for 40 years. It has “invested” €400 billion in public infrastructure. Infrastructure should, according to social market economic theory, directly enable economic growth and prosperity. This theory is core to the European Union’s actions and policies.

The stagnation of the EU economy, the failure of the 2000 Lisbon Agenda, the debt crisis in the Eurozone, and bailout of public sector borrowers (i.e. EIB’s borrowers and shareholders) demonstrate the utter failure of the approach of which EIB is a cornerstone.

The European Investment Bank has distorted capital markets by raising €400 billion at the risk of EU taxpayers, then investing it inefficiently in projects that increase taxpayers’ liabilities which do not bring economic benefit. It is a market-distorting anomaly that should be stopped, not expanded, so that resources can be allocated by the market. Instead EIB has an existence because it sits at the confluence of political objectives (politicians creating spending and the illusion of economic growth now by selling IOUs on future tax revenues) and the Basel Bank Capital Adequacy regime installed by politicians and favouring lending to two segments:

1. Real estate

2. Governments themselves

There are eerie parallels with Northern Rock, a market-distorting real-estate lender that convinced itself that its business was risk free. Northern Rock attained to a 25% share of new UK mortgages before it became illiquid. All its new money was borrowed from the capital markets, based on its credit rating, with very little in the way of own funds should things go wrong. It geared itself up based on the theory – backed by the Basel Capital Adequacy regime – that real estate lending is very safe and needs very little capital to back it.

When they did go wrong, the taxpayer had to step in. That is not necessary in the case of EIB because the taxpayers own it already and are exposed up to €232bn.

The European Investment Bank has geared itself up on the theory that lending to governments and the public sector is very safe and needs very little capital to back it, with, as a second string of activity, lending to SMEs upon which it does no credit analysis under the guarantee of commercial banks. Again – under the Basel Capital Adequacy regime – lending against bank guarantees is very safe and needs very little capital to back it.

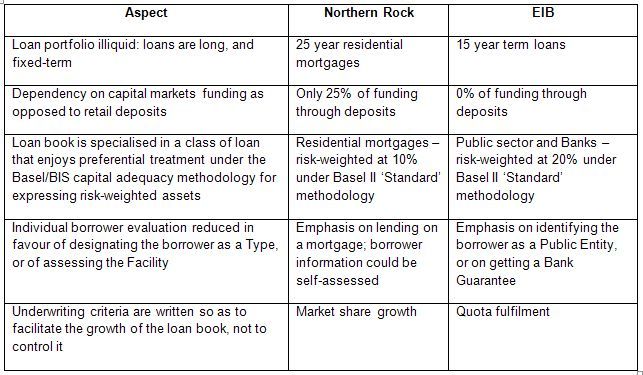

Moodys’ has recently put EIB on its watch list for possible downgrade, the first indication that all may not be so very rosy at the Bank. The eerie parallels between EIB and Northern Rock are as follows:

The European Investment Bank claims that its loans are “of the highest quality”. As of the end of 2010 it had outstanding loans to the public sector of the following countries, and it continued to build the loan book in 2011 at the same time as the sovereign borrowers in the same countries were having difficulty in raising funds in public markets:

Spain: €64bn

Italy: €43bn

Portugal: €21bn

Greece: €14bn

This amounts to €142bn of loans to subdivisions of countries with financial difficulties, where loan repayment has to be drawn from the same well as repayments of sovereign debt. This speaks of a misallocation of the European Union’s economic resources on the grand scale.

Bob Lyddon is Managing Director of the IBOS Association Central Office. IBOS stands for International Banking – One Solution. It is an association which fosters inter-bank cooperation. Currently active in 49 countries and rapidly expanding, its members include Santander, HSBC France, Intesa SanPaolo, KBC, Nordea and UniCredit Bank.

Explore more articles in the Banking category