EUROPEAN BANKS’ RETURNS REVEAL RELUCTANT RECOVERY

Published by Gbaf News

Posted on August 1, 2014

6 min readLast updated: January 22, 2026

Published by Gbaf News

Posted on August 1, 2014

6 min readLast updated: January 22, 2026

The long-awaited recovery of European banks has yet to happen, as SNL Financial’s ROE figures demonstrate.

Indubitably, the ROE numbers in our analysis make for depressing yet insightful reading.

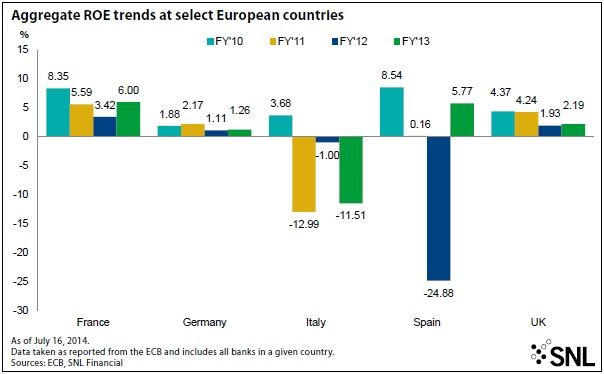

Between 2010 and 2014, the five major economies of France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the U.K. did not once see their banks achieve double-digit returns.

Given that a figure of around 10% is generally seen as the cost of capital for a bank, few banks in those countries have recently managed to earn their cost of equity. Indeed, the mainly traditional Italian and Spanish banks have clearly endured heavy loan losses during the long crisis-driven recession. Recapitalization, deleveraging and retaining dividends have been themes everywhere as losses were absorbed.

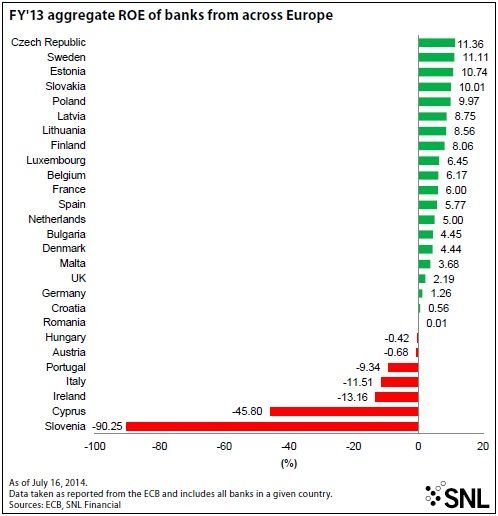

The smaller economies have fared somewhat better but far from all.

In 2013, only the Czech Republic, Sweden, Estonia, Slovakia and maybe Poland met their cost of capital, according to SNL data, while Slovenia, Cyprus, Ireland, Portugal, Austria and Hungary achieved negative to very negative returns.

Investors remain concerned about the level and quality of bank returns. J. Christopher Flowers, the private equity fund investor, told the Financial Times July 20: “All the stuff that has happened and all the rules we’ve introduced have depressed profitability and that is a real vulnerability. Nobody is going to invest in an industry with returns of 5%.” He further observed that it was impossible to turn banks into utilities and that bank crises would continue to take place.

Subjectively, the ROE figures look far worse than one might expect after a season of monitoring bank reports and presentations. Here, professional optimism does rule. It is hard to believe the picture is as bad as our figures show.

The reason is clear. Banks restate their returns to create underlying figures or core results. These typically exclude one-offs from litigation, fines and redress costs as well as the costs of restructuring and losses incurred on noncore assets either destined for sale or rundown. In the case of major provisioning for credit losses, it is useful to talk positively about the future and treat the past as another country.

Moreover, because the banks’ restated figures are calculated in different ways, they are not at all comparable. One bank’s restated 12% ROE is not the same as another’s.

By contrast, our figures for select European banks for the first quarter of 2014 are comparable, thus indicating their relative performance as well as their ability to pay dividends and retain not to mention expand capital.

By contrast, our figures for select European banks for the first quarter of 2014 are comparable, thus indicating their relative performance as well as their ability to pay dividends and retain not to mention expand capital.

One main exception to these findings comes from the Nordic countries, where the banking system manages to combine high capital and high returns.

Then there is Russia and Turkey, countries whose banks show high returns but are being affected by political turmoil and the prospect of weaker growth. Returns look destined to fall with international sanctions being imposed against Russia over the turmoil in Ukraine while domestic tensions remain in Turkey.Neither system is a picture of health.

The performance of OAO Sberbank of Russia looks strong but actually reflects a more troubled present. At one stage, in the not-too-distant past, the leading Russian bank was looking at achieving a 30% return on capital.

Thus, the question of when bank returns might again become healthy looms large — and bankers are now talking about running their business for returns.

French banks, which are widely seen to be among the strongest of the five leading economies, have unveiled ROE targets for 2016 or 2017; in the case of BNP Paribas SA and Société Générale SA of just 10% or higher. This is not much greater than their cost of capital and underlines how much work still has to be done — in what is a relatively strong economy where the banks enjoy good margins and demonstrate credible business models.

All measures are open to criticism. However, the return figures are satisfyingly capitalistic and illustrate why it might be better to be a bank depositor, creditor or shareholder. They calibrate the distance between success and failure.

“The bottom line is that the ROE is the number that ultimately matters; everything is linked to that, be it capital deficits or the discussions around the pressure on earnings,” Nick Anderson, a bank analyst at Berenberg, told SNL. “It is the bottom-line number.”

This number does illustrate the scale of challenges the banks face to recover, not least from the overhang of individual and state indebtedness in Europe. Anderson said: “The multiple problems of the banking system will take a long time to correct. None of the fundamental changes has really started to happen yet. The system has to pay off the debt — without regard to whose name is on the IOU, it is the system that matters.”

This number does illustrate the scale of challenges the banks face to recover, not least from the overhang of individual and state indebtedness in Europe. Anderson said: “The multiple problems of the banking system will take a long time to correct. None of the fundamental changes has really started to happen yet. The system has to pay off the debt — without regard to whose name is on the IOU, it is the system that matters.”

The problem of promoting growth when bank balance sheets are weak and impaired looks set to slow the European recovery. Indeed, since the French banks are looking to 2016 and 2017 for stronger returns, this state of affairs could last for a good while.

Mike Wolff, a credit analyst and strategist at Landesbank Baden-Württemberg, told SNL: “The sole countries that are functioning well are the Nordics. They are performing well, doing the right things. Some of them have core Tier 1 capital of around 20%. They really are super-solid banks.”

But generally, he continued, “the banking system has not yet reached the recovery phase; we must wait to see what the ECB-POLICY-RATES-82f6314e-6203-420b-bc8b-70a978546822>ECB publishes [in the autumn] before we really know about asset quality. No new risks can be undertaken and without new risks, there will be no earnings [growth].”

There are some signs of recovery. Among the banks appearing in SNL’s first-quarter 2014 table, HSBC Holdings Plc, KBC Group NV and Lloyds Banking Group Plc stand out because their earnings almost certainly sufficed to cover their cost of capital. This looks a clear improvement on the Belgian and British systems in 2013. The roll-call of underperformers remains, however, long and impressive.

This picture of present difficulties has not prevented a recent recovery in peripheral banks share prices. However, over five years the STOXX Europe 600 Banks index is virtually unchanged.

Wolf said: “The bank shareholders have had bad years and they will probably continue to see bad years. They are the losers, that is for sure.”

Explore more articles in the Top Stories category